Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb

…. thus goes a famous nursery rhyme from our childhood. How is it relevant to version control? In this post, you are going to imagine yourself as an author of the afore-mentioned nursery rhyme, working with a few more colleagues. Using that example, we will see how version control software works.

Imagine that Nancy, Tommy and you are authoring the poem ‘Mary had a little lamb’. You are going to be using version control software. Why use version control?

- First of all, the three of you cannot work on a single file together. Conflicting changes from all of you will make each of you step on each other’s toes. Instead of getting a poem smoothly written, you will be constantly writing on top of each other’s work and getting nowhere. Version control makes sure that each of you has his/her own copy of the poem that you will modify locally and then make sure that the changes are available to everyone.

- The poem will be written in the form of small milestones and the milestones can be extracted seperately. If you decide that your last few changes are not worth it, then you can revert to the last saved milestone and resume work from there. Each such milestone is called a commit.

So onward we go.

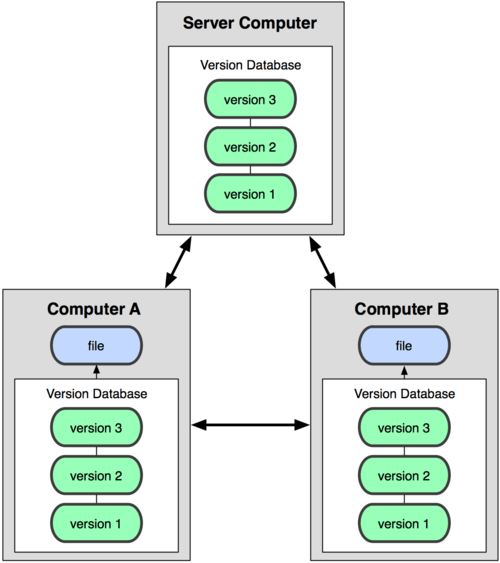

A central ‘repository’

Complicated word. But here is what it means. As the three of you work on the poem, you will need a central space where all of you will keep your latest changes. Before you begin your work everyday, you have to make sure that the lines written by your co-authors are part of your copy of the poem. And at the end of the day, the lines written by you should be made available to others, so that your lines can be added to their copies. The place where you make all of your changes available is the central repository. The central repository is on a machine which is accessible to all of you. Usually it is a simple HTTP URL such as https://our-nusery-rhymes/mary-had-a-little-lamb.git. All three of you will be given access to the central repository using authentication such as username-password or phone number – OTP, etc.

‘Cloning’ to a local repository

The central repository resides on a machine that is usually somewhere on the Internet. However, for the three poets to work on the poem, their individual computers must have the entire copy of the repository. The central repository is downloaded in its latest form to the local computer. Like the central repository, this local copy too has all the milestones of the poem written so far. The local repository acts as a sandbox on which each poet will work until they are ready to ‘push’ their changes to the central repository. We will see the process of ‘pushing’ in a bit.

‘Committing’ changes

The most important process of version control is committing changes. This is the process by which a poet is satisfied with his/her version of the poem so far and is ready to save those changes permanently so that others will be able to receive those changes. You can think of a repository as a database table and each commit as a record. The commits track each version of the poem as the poets work on it.

But, here is something specific to version control commits. They track ONLY changes across the two milestones of the poem. Each computer’s version control software works through the changes in each milestone and shows the poem to the poet in its current form.

To illustrate with an example, let’s assume that Nancy starts first, writes some part of the poem and commits the first version.

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb.

Mary had a little lamb.

My fair lady.

“Oops”, thinks Tommy, “that doesn’t sound right.”

He edits the third line to, “Its skin was white as snow.” and commits his changes. Against his commit, the version control software does not store all 3 lines, it simply saves Tommy’s changes. Commit 2 simply says,

My fair lady. Its skin was white as snow.

“Oops”, you think, “You can’t see a lamb’s skin. What you see is the fur.” So you make your correction. That’s the third commit.

Its skin fleece was white as snow.

Let’s review the three commits yet again.

Commit 1:

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb

Mary had a little lamb.

My fair lady.

Commit 2:

My fair lady. Its skin was white as snow.

Commit 3:

Its skin fleece was white as snow.

The repository now has 3 commits. We will see how commits are ‘replayed’ to bring your version of the poem upto date with whatever is in the repository.

‘Pushing’ changes

When you commit a change, it only gets saved to your local repository. The changes do not go to the central repository. Your changes are not seen by Nancy or Tommy. Both of them still see Tommy’s version saying ‘skin’. You need to push your commit #3 to the central repository.

‘Pulling’ changes

After you have pushed your changes. Nancy and Tommy need to pull those changes. So they issue a ‘pull’ command to the central repository. The repository promptly sends them the latest changes, i.e. commit #3 that was made by you.

The replay process

When Nancy pulls from the central repository, she gets the changes made by others. In our example, she would receive commits #2 and #3 made by Tommy and you respectively. The changes in the two commits are ‘replayed’ on her poem. Replaying is the process of applying the changes specified by each commit one after the other so that the latest content can be produced from them.

Here’s is the process by example.

If Nancy is on commit #1, she still has her poem saying ‘my fair lady’. But if she pulls, then the following two commits are applied to her copy of the poem.

My fair lady. Its skin was white as snow.

Its skin fleece was white as snow.

Now her copy looks like everyone else’s.

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb.

Mary had a little lamb.

Its fleece was white as snow.

Conclusion

The three poets are happy with how the poem has progressed so far. Using a repository, commits, pushing and pulling, the three poets have the same copy of the poem. Their version control software uses the concept of commits, wherein only changes across two versions are stored and not the entire poem again and again. This makes it fast to download and apply changes.

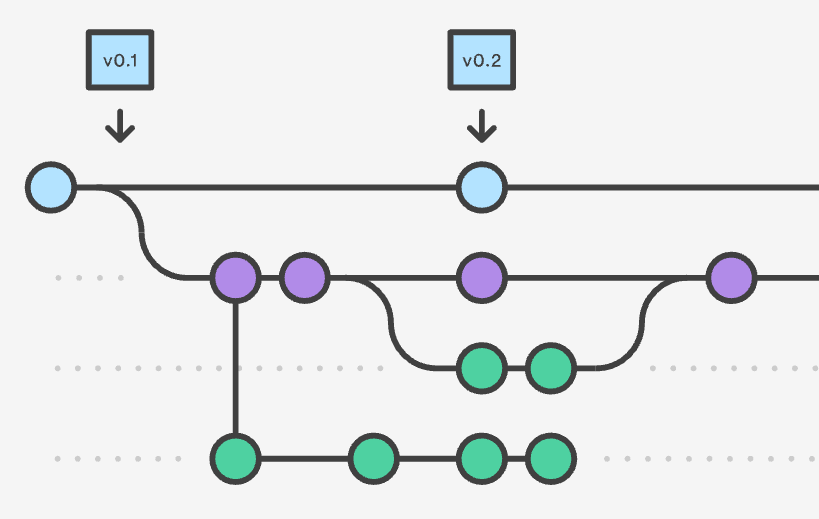

The three are now ready to grow the poem. But they will use advanced concepts like branching, merging, fetching and resolving conflicts. You will get to learn about those in part 2 of this series on version control software.

One thought on “How version control works: Basics”