Did you read the title of the post correctly? Am I, a software engineer, really encouraging you to reject writing software solutions? Yes indeed I am. There are times in your career when you’ll need to evaluate if a particular problem really requires writing a new piece of software. Sometimes, you’ll find that a NO is the best answer for everyone. Continue reading “When to reject creating software solutions”

Tag: software engineering

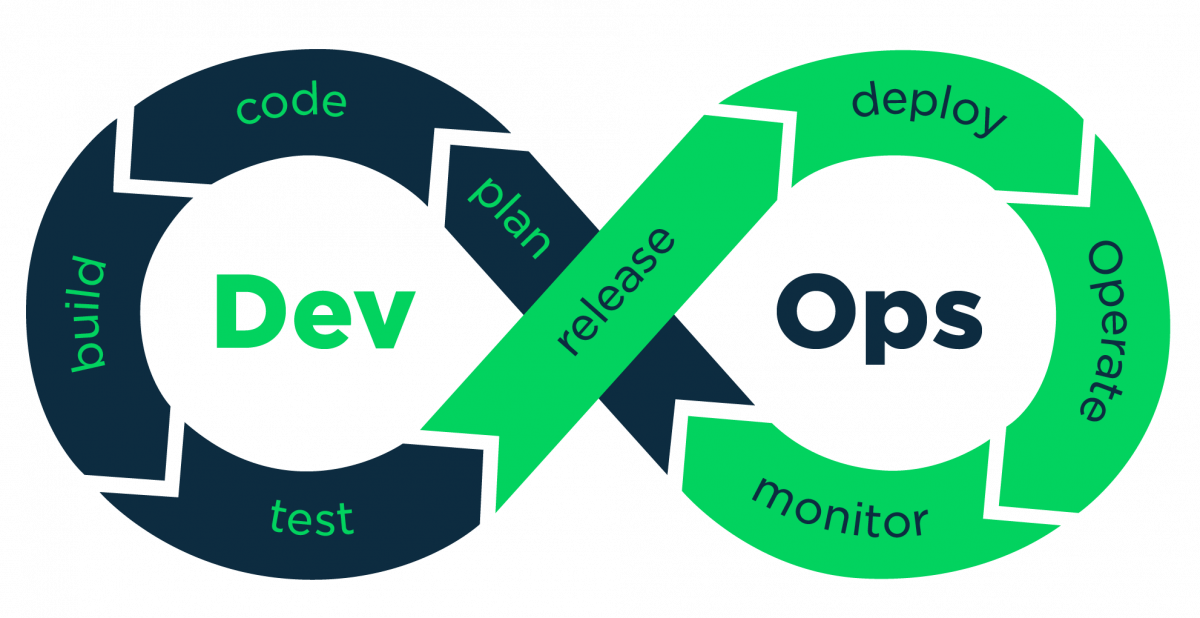

Understanding DevOps: An interview with two practitioners

As one of the latest catchwords in the world of software, DevOps is a term that has been growing in popularity over the last decade. Is it yet another meaningless jargon which will fade away when the fashion wears off (Blu Ray discs, are you listening?!). Or is it something really useful, practical, helpful and here to stay for generations to come?

To understand what DevOps is, how it works and how it helps the people who use it, we sat down with software developer Dave and operations manager Oprah to understand how they use DevOps in their company, FutureSoft Solutions. Continue reading “Understanding DevOps: An interview with two practitioners”

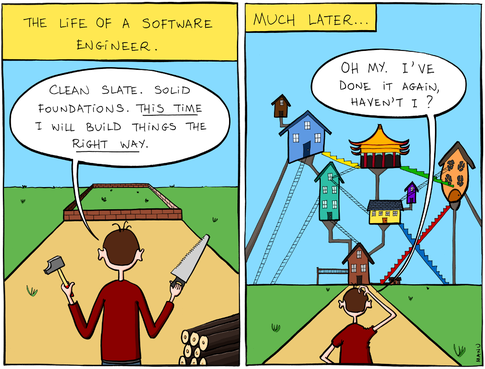

Starting a software project on the right foot

Software projects are complex. Often the goal of an application looks simple, but as time progresses, the participants realise how complex the it actually is. Usually they fail to consider every type of input and the corresponding output. Fringe cases are often ignored and suddenly need to be accounted for. The most overlooked flaw is a lack of communication between the one who wants to use the software and the one who builds it. Requirements are not fully discussed and expectations are not fully set.

Most projects are difficult because they are not started the right way. The project starts in a direction that has already drifted from the desired outcome. It continues to drift until a lot of changes or even a ‘scrap and rewrite’ are needed to bring it back to course at a much later stage. In this post, I would like to discuss the points which should be taken care of so that you start a software project the right way. Continue reading “Starting a software project on the right foot”

6 practices that keep your software masterpiece from seeing the light of day

Software engineers switch between two modes: painful perfectionists and band-aid stickers. During the start of a project, software engineers discuss things to painful detail on whiteboards, Post-It notes, restaurant napkins and even glass doors. This eats away precious time that could have been spent on actual development. But as the deadline looms, the whiteboards and glass doors are rubbed, Post-It notes are torn apart and restaurant napkins are trashed. The plans are chucked in favour of anything that makes the application work.

Often, the released solution has plenty of duct tape code that holds the functionality together. After all the over-planning, duct-tape coding is the only thing possible in the limited time that the programmers leave for themselves. Software teams hardly release anything during the early phase of a software project as everything is put in meticulous detail on paper only. But as the deadline approaches, frenetic releases are made everyday or even every few hours, causing confusion among the developers, project managers, testing teams and the clients.

Continue reading “6 practices that keep your software masterpiece from seeing the light of day”

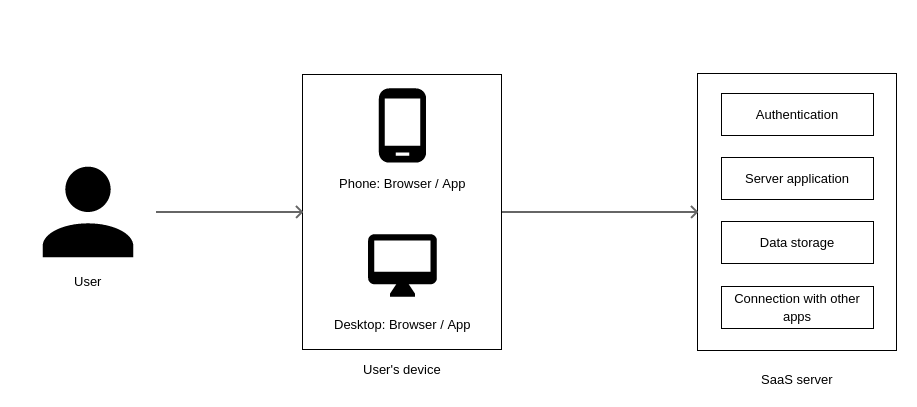

Understanding Software-as-a-Service (SaaS)

The world of software and information technology throws up jargon at an explosive rate today. It is hard to keep up with them and even harder to understand what they mean. One such term is SaaS or Software as a Service. Let me explain what it means and how it is important to you.

What is SaaS?

SaaS refers to a software that MANDATORILY has the following properties.

- The core of the service runs over the Internet on a server, while the user works with a bare-bones tool on his/her device.

- Usually nothing is installed on the user’s device and a browser is used to connect to the service. Even if something needs to be installed, it is just a small app with a user interface and a set of functions that connect to the Internet to exchange data with the service’s server. No service functionality resides inside the app.

- No storage happens on the user’s device. All of the user’s data is stored on the server securely.

- The user needs to connect to the Internet and login to an account in order to use the service and access his/her data.

- Due to the service being on the Internet, a user can access his/her data from any device from any location, be it on a smartphone from a car seat, on the home desktop computer or on a laptop from a resort.

- As a result, changes made from one device are almost immediately available on another device.

- Functionality can be extended on a daily basis because all the functional code is on the server. The user doesn’t have to install a new version on his/her device. In case of a web application via a browser, even the UI can be updated frequently without the user having to install anything.

This is contrast to a traditional desktop software application, where a huge software application with UI and all the functionality is installed on the device’s storage, all the files are stored locally on the device’s storage device and the user needs to remember to copy the files to a portable storage unit such as a thumb drive in order to transfer them from one device to another. Changes also need to be synced among devices every time. Changes to functionality are released as a new version of the application and they too need to be installed on the server.

Additional features

Apart from the above features which are mandatory, Saas MAY provide some of the following features

- Limited offline access to use the service when Internet is down.

- The ability to download files to local storage.

- The ability to connect one SaaS to another in order to use the features / content of one in another. E.g. Pixlr can use your Google Drive as storage.

- Ability to share your files with other accounts as read-only or read/write.

Examples of Saas and equivalent desktop applications

Real examples of Saas are as follows.

| Desktop | Saas |

|---|---|

| Microsoft Word | Google Docs |

| Microsoft Outlook | GMail |

| Adobe Photoshop | Pixlr |

| Files and directories | Dropbox |

Where SaaS fails

- The biggest failure of SaaS is when going for long periods of time without Internet. While some SaaSes allow you to edit your content offline, your content will not be synced to the server. So if another person makes changes to the same files from another device, there will be conflicts.

- An insecurely set up SaaS can cause a risk where contents can be snooped and even downloaded by unauthorised persons.

- All the data is in the hands of the company providing the SaaS and not in your control. A change of policy or an infrastructure collapse can lead to loss of your data.

What you need to build your own SaaS

If you are a company who wants to build your own SaaS, the following should be your technical know-how. There are further requirements such as strong policies and legal agreements which are beyond the scope of this post.

- Setting up your own server either in physical form or on a cloud service such as Linode, Rackspace, Amazon Web Services or Google Cloud Compute.

- Complete knowledge of HTTP protocol. The app on the device and the server communicate using HTTP.

- Securing your HTTP communications using HTTPS.

- Programming on the server side using one of NodeJS / Python / Java / Ruby / PHP / .NET.

- Using server side file system and databases for data storage.

- Using OAuth to validate users who log in and to reject users who are either no signed in or are using invalid credentials.

- Using OAuth to allow other apps and users to access a given user’s data.

- If you are making a web application for the user’s browser, then your knowledge of HTML, Javascript and CSS should be strong.

- If you are making platform-specific apps, then here are your requirements.

- Java / Kotlin programming for Android

- Swift programming for iOS

- .NET programming for Windows

- Cocoa application programming for MacOS.

- QT / GNOME using C++ or Python for Linux.

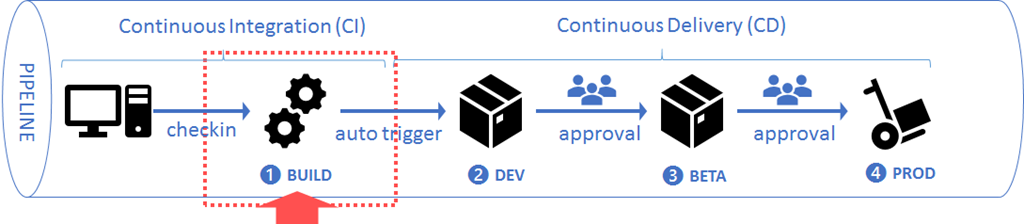

- Usage of Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery to roll out new versions.

- System administration for the following requirements.

- Monitoring the server to make sure that things run smoothly.

- Frequent backing up so that data can be recovered.

Conclusion

Being the trendsetter of the last decade, SaaS is now commonplace since 2010 or so, when rich web applications, Android and iOS took the world by storm. There was a need to access apps and their data from anywhere to which SaaS provides the solution. And that need and the success of SaaS is not going away anytime soon.

Database or no database?

What do you do when your application needs to store something? Are you the type of developer or company that habitually jumps to create a database everytime you see that an application needs to store something permanently? Worse, are you the type of programmer who stores binary things like images, music, videos and ‘what not’ inside databases too?

On the other hand, are you so petrified of and averse to databases that you store everything in Excel, comma seperated or JSON files?

In this post, I put forth some rules I use to decide what goes into databases and for what type of data you should consider a different data storage.

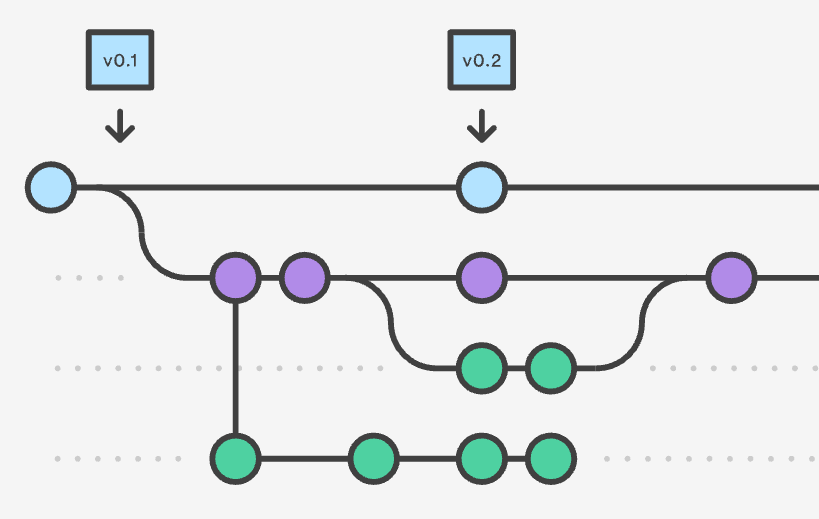

How version control works: Basics

Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb

…. thus goes a famous nursery rhyme from our childhood. How is it relevant to version control? In this post, you are going to imagine yourself as an author of the afore-mentioned nursery rhyme, working with a few more colleagues. Using that example, we will see how version control software works.

Dipping your toes in the water with test-driven development

Akshay is anxious to have cutlets. He can’t wait to sink his tooth into the cripsy, brown delicacies. He quickly boils some potatoes in a pot, mixes them hurriedly with some chilly, salt and pepper, pats the mixture into round shaped patties and sautes them on the pan greased with oil. Finally, he eats them. Oops. The potatoes are only half-boiled. He has added too little chilly, too much salt. The oil had not heated properly before Akshay tossed the cutlets in it for shallow frying. Some cutlets are still raw. Akshay thinks to himself: “Next time I should test the results after each step of cooking.”

Bharani is more methodical. She starts with a skewer. The skewer bounces off the surface of the potato. “So this is how hard they are”, she thinks, “They need a 10-minute boiling. After that, the skewer should go 2 inches inside”. After the potatoes are done, she tests with the skewer again and is satisfied with the texture. She mashes them and puts a small sample of the mash into her mouth. The bland taste gives her an estimate of how much spices should be added. She starts with a teaspoon of chilly and salt, kneads the mash well. After 10 seconds of mashing, she tastes a sample. She adjusts the chilly and salt as per her liking and then pats the mash into round shaped patties. Next she heats some oil on a pan. She waits until the oil sizzles. Then she drops a tiny piece from one of the patties and checks how it fries. The piece comes out golden brown and cripsy. Now Bharani is ready to lay all the patties on the pan. In the end, she enjoys some tasty cutlets.

Continue reading “Dipping your toes in the water with test-driven development”

Compilers and Interpreters

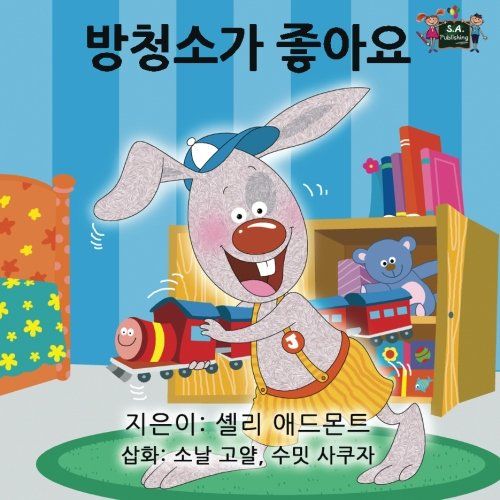

Khushi loves to write children’s stories. She has written several stories in English in her country India. Muskan, a friend of Khushi, works for Samsung. She goes on a business trip to South Korea and takes her young daughter along. She has some children’s books in one of her bags. A local colleague loves the book and asks Muskan if her friend can make the books available in South Korea in Korean.

Khushi is delighted at the opportunity and is ready for a trial book tour in Seoul, where she is to showcase three trial stories to South Korean children. If they love it, there’ll be a deal with a publisher. However she has a problem. She doesn’t speak a word of Korean. The children of South Korea aren’t comfortable with English. So Khushi has two choices. She can use help, translate the three stories into Korean and take the Korean versions with her so that the children can read them on their own. Otherwise she can seek someone in Seoul who speaks both the languages fluently. Then she can read the story line-by-line in English and the interpreter can translate each line into Korean for the children at the same time.

What does children’s books have to do with our topic today? There are two types of programming languages in software. Some of them use a compiler and some use an interpreter. Using the children’s books as an example, we will learn how the two work.

Compiler: When Khushi takes a translated book to South Korea

Khushi decides to do the hard work upfront. She hires a translator on Upwork and gets the three stories translated to Korean. She can then take the Korean books to South Korea and hand them to the children, who can read the books without help. She can take the Korean books to as many Korean communities as she likes, without having to look for a translator every time.

However, Khushi faces the following issues. On one hand, she needs to keep the English versions as her source products, whereas the Korean versions are her by-products. Instead of just 3 products (the original 3 stories), Khushi needs to maintain 6 products (including the 3 translations).

If Khushi finds the need to rewrite several parts of her stories, she must discard the Korean translations and have them done again. Thus, the process of translating beforehand is too sensitive to changes.

If someone invites Khushi to Netherlands, then the Korean translations are useless. She has to find a Dutch translator who will translate her books to Dutch. That will add 3 more products to her collection, taking the total to 9.

Finally, translation is a lot of work upfront. The entire book has to be translated from start to finish so that it can be used in South Korea. The time taken for translation will depend on the length of the stories and the complexity of the sentences used.

This is how a program using a compiler behaves. Let’s assume that you write your computer program in C or C++. A computer cannot understand either of those two languages. It can understand only something called machine language. Machine languages are different for different types of computers, just like Korean is to South Korea and Dutch to Netherlands. E.g. the machine language understood by a desktop computer is different from that of a mobile phone and that of a microwave oven. The microwave oven cannot understand the machine language meant for a desktop computer, the same way a Dutchman cannot understand Korean.

Once you write your program, you need to run a compiler to translate the program into the machine language of the target machine. You need to compile one copy for each type of computing device you wish to run the program on. You need to maintain each compiled copy along with your original program in C/C++. The original one is for you to develop and grow your program in the future, whereas the compiled versions are for distribution. As long as two machines understand the same machine language, you can use the same compiled version on both. This is similar to the way that Khushi can use the Korean translation at Seoul as well as Incheon, but not at Amsterdam.

Every time you make changes to your program, you need to re-compile to all the target machine language versions, discard the older compilations and distribute the new ones to the target machines.

Interpreter: When Khushi hires an accompanying translator within South Korea

In this scenario, Khushi does not get her book translated upfront. She takes the English book with her to South Korea with the promise that she will have an interpreter accompanying her all the time. She reaches this agreement with Netherlands too. As long as the two countries keep their end of the promise, Khushi does not need to get any translation done upfront. Her luggage to both the countries includes the three stories that she wrote in English. When Khushi reaches the target community in South Korea, she pulls out her stories and starts reading them line-by-line. As soon as she finishes reading a line, the interpreter speaks the whole line in Korean, thus reaching Khushi’s audience.

Khushi can makes as many changes to the stories as she likes. She is guaranteed that her latest version will be translated line-by-line during her next story-reading session.

But life isn’t all rosy with this approach too. Khushi needs to make absolutely sure that the target country has a translator available to her. Without the accompanying translator, her English books are just useless.

Also, Khushi needs a translator every time she wants to showcase her stories to the same community or different communities inside South Korea. Just because her translator translated her story orally line-by-line doesn’t mean that anything was recorded in writing. The line-by-line translation needs to be done all over again.

Finally, take the case of a country like Kenya or Congo. These countries are poor and translation is not a lucrative job. The quality of translators is usually mediocre, with limited vocabulary. The result may not do justice to Khushi’s hard work.

This is how interpreted languages like Javascript, Python and Java work. The program in the original language is directly copied to as many target machines as required without undergoing any compilation, with the promise that the target machines have the interpreter of the required programming language installed. The programmer can make as many changes as required and immediately copy the new version to the targets, which will use the new version during the next run.

If the target device does not have an interpreter for the programming language, then the whole program is useless. There is no way to run it in that device.

The program interpreter behaves similar to Khushi’s language interpreter. It converts the program instructions to machine language line-by-line, but doesn’t note down the translations. As a result, the conversion is done every time the program is run.

A hybrid approach

What if Khushi carries the English versions to South Korea, but the interpreter also notes down the Korean version at the same that she translates line-by-line. By the time the interpreter is finished translating to the first community, there will be a newly written Korean version that Khushi can simply distribute to the other communities in the same country. Khushi doesn’t have to get everything translated upfront before leaving for South Korea. Nor does she have to take her interpreter with her everywhere. Khushi needs to remember one thing. She needs to take her interpreter along when changes are made to a story. The interpreter can then note down the Korean translation of the new version of the story when reading it for the first time to a Korean community.

Modern interpreters behave this way. They read programs line-by-line and issue the converted machine language instruction to the processor. But they also note down the conversion into a special area called the interpreter cache. As long as the source program hasn’t changed, the interpreter will take instructions from the cache rather than reading from the source language and translating yet again.

Comparison of compilers and interpreters

Here is a tabular comparison of compilers and interpreters.

A compiler needs to be installed on the machine where the program is developed.

An interpreter must be installed on every machine that the program needs to run on.

The program in the source language, e,g. C/C++, must also be maintained only in the development machine.

The program in the source language must be present on every device where it is to be run.

The source program must be converted into a machine language translation, which must be copied to every device. This must be done for every type of computing device.

The source program is copied as it is to every device where it should run. The same source is copied to all types of computing devices.

The entire program must be converted to machine code up-front before copying to the target machine and running. For a huge program such as an operating system, this may take several hours.

The interpreter picks up one line from the program and converts only that line to machine code. This is done for every line until the entire program is interpreted.

Once a program is converted to machine code and copied to the target device, no more translation takes place.

Since the program exists in source form, the interpreter must translate every line every time. But if an interpreter has a cache, then it only needs to translate once.

Which approach should I use?

There is a reason why 99% of the programming languages today are interpreter-based. The developer needs to maintain only the program in the source code and does not need to learn the tools to convert it to machine language form. The onus of converting lies with the company that writes the interpreter for the various computing platforms.

There are two reasons why a developer would want to look at writing some modules in compiled languages.

- If you are running your program on a device that has very little storage and memory, it may not be possible to fit the interpreter into a low-capacity disk and then load it into limited memory. A compiled program, which is already in machine code for that device, would not need the interpreter at all. This is similar to Khushi’s situation in Kenya where good interpreters aren’t available.

- If you are running a program that needs to be really, really fast, then the cost of translating every line before it is executed will catch up to you and make the experience bad. You will never see video editors or 3-D modelling apps made in Java or Python. The delay in interpretation will visible cause the frame rates to drop below 25 frames per second and you will notice what is called ‘jank’, i.e. video frames being delivered slower than what the eyes perceive as motion. As a result, video applications or applications that need real-time response are always written in compiled languages. Directly reading machine code is much faster than interpreted code.

Conclusion

Compiler and interpreters follow two different approaches, but their goal is the same. Both convert a program from it source language to something that a computing device will understand. It’s just that a compiler does it with the approach of someone setting curd from milk, i.e. starting well in advance before the product is used, whereas the interpreter follows the approach of someone who chops herbs right before tossing them into a pan, just in time, so that they don’t go stale.

Build a pipeline to success with CI/CD

Meet Laura. She’s a popular author and has written 25 books. She’s been writing for 10 years. It takes her about 6 months to roll out a book, from draft to publication. Her books are on an average 150 pages long.

Continue reading “Build a pipeline to success with CI/CD”